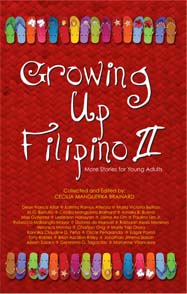

Please excuse me while I celebrate. I’m privileged to announce my latest short story “Here in the States” is included in the PALH anthology, Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults, edited by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard. Please consider this wonderful collection as a holiday treat for yourself, your family, any friends who love good stories, and any teachers or librarians who might be interested. You can get your copy through Amazon.com, or Barnes & Noble. I’d greatly appreciate if you’d please spread the word and would love to hear your reviews.

The San Francisco book launch takes place January 16, 2010. More information will be forthcoming or you can follow the updates on the PALH blog or this blog.

Thanks so much for all your support and encouragement!

LISTED IN AMAZON.COM GROWING UP FILIPINO II: More Stories for Young Adults

DISTRIBUTED BY: Ingram, Baker & Taylor, Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, among others

PUBLISHED BY:

PALH

P. O. Box 5099

S.M., CA 90409

Tel/fax: 310-452-1195; email:palh@aol.com; palhbooks@gmail.com;http://www.palhbooks.com

BOOK DESCRIPTION: Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults is the second volume of the Growing Up Filipino series by PALH. In this collection of 27 short stories, Filipino and Filipino American writers explore the universal challenges and experiences of Filipino teens after the historic events of 9/11. The modern demands do not hinder Filipino youth from dealing with the universal concerns of growing up: family, friends, love, home, budding sexuality, leaving home. The delightful stories are written by well known as well as emerging writers. While the target audience of this fine anthology is young adults, the stories can be enjoyed by adult readers as well. There is a scarcity of Filipino American literature and this book is a welcome addition.

CONTRIBUTORS: Dean Francis Alfar, Katrina Ramos Atienza, Maria Victoria Beltran, M.G. Bertulfo, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, Amalia B. Bueno, Max Gutierrez, Leslieann Hobayan, Jaime An Lim, Paulino Lim Jr., Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor, Dolores de Manuel, Rashaan Alexis Meneses, Veronica Montes, Charlson Ong, Marily Ysip Orosa, Kannika Claudine D. Peña, Oscar Peñaranda, Edgar Poma, Tony Robles, Brian Ascalon Roley, Jonathan Jimena Siason, Aileen Suzara, Geronimo G. Tagatac, Marianne Villanueva

BIO OF EDITOR: Cecilia Manguerra Brainard is the award-winning author and editor of over a dozen books, including the internationally-acclaimed novel, When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, Magdalena and Acapulco at Sunset and Other Stories. She edited Growing Up Filipino: Stories for Young Adults, Fiction by Filipinos in America, and Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and co-edited four other books. Cecilia also wrote Fundamentals of Creative Writing (2009) for classroom use. She teaches at UCLA-Extension’s Writers Program.

![[Image]](https://i0.wp.com/harpers.org/media/image/blogs/misc/caravaggio-bacchus-1596.jpg)